We’ve been here before.

In the wake of a series of mass shootings involving semi-automatic rifles, the cry for a ban on the manufacture and sale of so-called “assault weapons” has continued to rise in frequency and volume. After the Highland Park massacre, the local state’s attorney and now Governor JB Pritzker have publicly called for both state and national bans, with the latter calling for a special session of the Illinois legislature to address Illinois law to that effect.

The emotion sparked by each successive incident, with the horrifying scenes of bloody bodies and people running in terror – especially children – make such an outcry completely understandable.

However, if the objective is to decrease both the number and lethality of such incidents, and leaving aside the obvious Second Amendment issues involved in such a ban, it would seem prudent to first assess whether such a ban would be effective in achieving that objective.

Fortunately, it is unnecessary to rely on pure speculation. The fact is, we have been down this road before and can learn from that experience, if we so choose. From 1994 to 2004, the United States had a federal “Assault Weapons Ban” (AWB) in place, the main elements of which were pretty much identical to what is being called for today – banning the manufacture and sale of so-called “assault weapons” and “high-capacity” magazines (defined as magazines that carry more than 10 rounds of ammunition). Note: neither the previous AWB nor current proposals involve confiscation of “assault weapons” already in existence – roughly 20 million in the United States.

First, a bit of context:

- According to federal statistics, rifles of any sort, not just “assault rifles,” are involved in approximately 3% of homicides in the United States.

- By far, the most common weapon used in homicides in the United States is handguns. Rifles (again, of any sort, not just “assault rifles,”) rank below “hands, fists and feet” as weapons involved in homicides.

- An analysis of the last ten mass shootings (ending with Highland Park) indicates that the weapon of choice is split 50-50 between rifles and handguns. (It should be noted that in virtually all of these instances, numerous warning signs existed prior to the incident.)

Numerous studies have been conducted by both private and public entities to assess the effectiveness of the 1994 AWB, the most prominent of which include the Department of Justice, Rand Corporation and the Centers for Disease Control.

Without exception, the identified reports indicated that it was not possible to arrive at any definitive conclusions:

- Rand – “Considering the relative strengths of these studies, available evidence is inconclusive for the effect of assault weapon bans on total homicides and firearm homicides. We also identified one qualifying study that estimated the effects of high-capacity magazine bans on firearm homicides and found uncertain effects (Moody and Marvell, 2018b), leading us to find that there is inconclusive evidence for the effect of high-capacity magazine bans on firearm homicides.”

- DOJ (Via National Institute For Justice) – “The decline in the use of AWs (“assault weapons”) has been due primarily to a reduction in the use of assault pistols (APs), which are used in crime more commonly than assault rifles (ARs). There has not been a clear decline in the use of ARs, though assessments are complicated by the rarity of crimes with these weapons and by substitution of post-ban rifles that are very similar to the banned AR models.”

- CDC – “Evidence was insufficient to determine the effectiveness of any of these laws.”

What About The Recent Rise In Mass Shootings?

The increase in mass shootings is indeed frightening. But, again, context is critical in assessing whether an AWB would be effective in changing its trajectory.

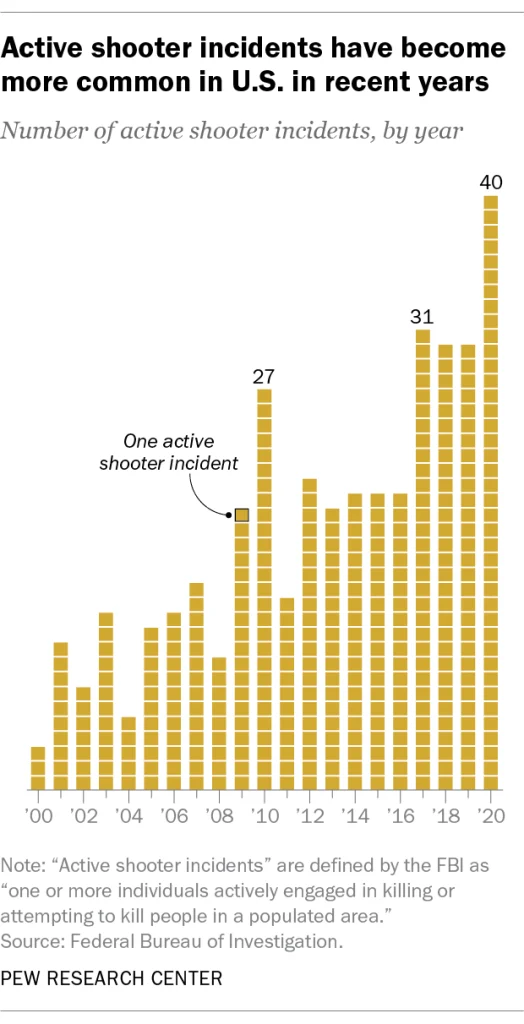

Consider the chart opposite. Obviously, the period 2017-2020 jumps out, and it’s reasonable to assume that years 2021 and 2022 would be roughly equal to or higher than 2020.

But two questions arise when assessing this increase.

First, the definition of “mass shooting” (or, in the FBIs nomenclature, “active shooter incidents”). Different sources define “mass shootings” differently, which, unsurprisingly, leads to different results. Probably the biggest distinction between the various definitions is whether shootings are undertaken in the commission of another crime (most importantly, gang violence). If we are assessing mass shootings similar to the ones at Highland Park, Uvalde, etc., including gang violence and other violent felonies like armed robbery doesn’t make sense. The chart opposite includes ALL shootings wherein one or more individuals were actively engaged in trying to kill people in a public place. That includes gang activity.

Let’s compare that to two other databases that exclude gang and similar activity. In 2019, Mother Jones identified only 19 mass shootings compared to the 30 in the chart opposite. The Mass Shooter Database (The Violence Project, undated) shows even fewer that year, 9. In addition, the fact that mass shootings are still so relatively rare creates major problems in quantification, much less assessment. As Rand noted: “Chance variability in the annual number of mass shooting incidents makes it challenging to discern a clear trend, and trend estimates will be sensitive to outliers and to the time frame chosen for analysis.”

But assuming that we are, if fact, experiencing a sharp increase in mass shootings, the second question becomes “why?” The 1994 AWB ended in 2004. The landmark Heller decision from the Supreme Court, which clarified that the Second Amendment right to bear arms applied to individuals, was handed down in 2008, 15 years ago. What has happened in the last few years to cause such a significant spike in such incidents? Or is this spike, if indeed it is a spike, the “chance variability” described by Rand? Is there any evidence at all to suggest that the popularity of rifles like the AR-15 has anything to do with it? So far, no such evidence appears in the research.

Summary

Despite the almost universal call from politicians and advocacy groups to address gun crime and, specifically, mass shootings by instituting “assault weapons” bans, such a solution is long on emotion but short on evidence. We have been here before in terms of an “assault weapons ban,” and its results were, at best, inconclusive. It certainly didn’t stop such incidents.

It would appear, from the evidence, that other, perhaps more intractable problems – child neglect, mental illness, poorly-written and/or poorly-executed laws, lack of police training, etc. – are driving these tragedies. In short, being skeptical of the superficially “easy” solution is always a good policy.